Emotions in Paper and Ink

Primafila’s Japan correspondent Charles T. Whipple sets out to learn about the Japanese art of calligraphy.

By Charles T. Whipple

By Charles T. Whipple

Photos: Hakusen Shodokai

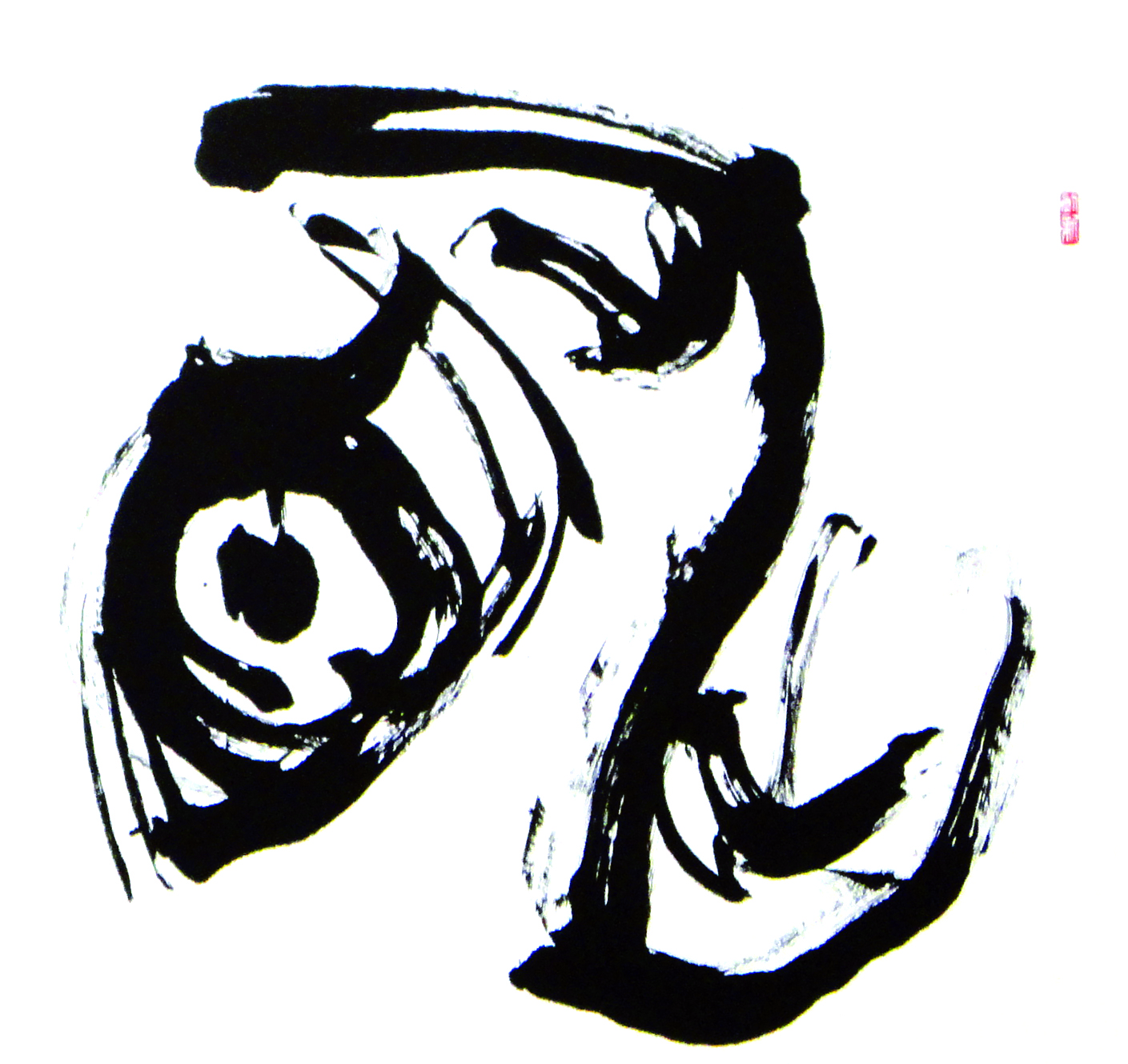

The day before I was asked to put together an article on Japanese calligraphy for a publication by a Primafila client, I ate lunch at a favorite Japanese restaurant in town. A piece of framed calligraphy hung on the wall behind the cash register podium. Written on so-called rice paper (which is actually made from fibers from the bark of certain trees), the character portrayed meant “water.” On pure white paper, the calligrapher had made the character with very watery ink, so the image was soft and wet-looking. Then, in two places, dark drops of ink furthered the image of water, looking much like a pond looks when a small stone is tossed into it. Symbolically, that single character impressed me with how much calligraphy affects the emotions of the person reading it.

The request for an article on calligraphy and its implements came, and the very strong image from the day before colored my reactions. I knew the art must be explained by a master.

Strangely, that day I received a thank-you note. It too was written on handmade paper with a fine brush. Although I know who sent the note, I do not know who wrote it. But whoever it was, the brush control was impeccable. Sometimes, thank-you notes are written by professional calligraphers, or by people who have spent years at calligraphic writing.

Unfortunately, while I write by hand, especially when I am writing fiction, my hand is in no way even close to calligraphy. Further, I personally have never studied the art of writing Japanese characters with ink and brush. I knew I had to have some help to find the right spokesperson.

For several years, I have acted as the steering committee chairman for a high school English speech contest, and in that capacity, made the acquaintance of Fumiyoshi Komatsuzaki, one of the city of Chiba’s young assemblymen. Over lunches of fresh seafood and sukiyaki beef, we discussed the issue, and Komatsuzaki—through his network of acquaintances—found Manjo Taneya, master calligrapher of the Hakusen Shodokai, who agreed to meet Komatsuzaki and I at his calligraphy school.

We arrived at 10 a.m. and were ushered into a simple Japanese style room with tatami mats on the floors. Several examples of the master’s calligraphy graced the walls. In racks at the end of the room, hundreds of brushes hung quietly awaiting their master’s touch. Some had waist-high handles and great brushes of horsetail hair. Others were tiny and slim enough to scribe a line just one-tenth of one millimeter wide.

In demonstrating the amazing possibilities of calligraphy, Taneya chose his brushes with care, but used a bottle of commercial ink. I asked him about that, and he said, “If I were writing something important, either for show or to communicate something special to someone special, I would carefully prepare the sumi ink in an ink stone with a high-quality ink stick. It would have to be the right texture and leave the right image on the paper, so ink preparation is vital. Here, we are just showing examples so commercial stuff is OK.”

The master traced lacy characters on a sheet of tan washi paper. Komatsuzaki drew a deep breath and turned to me. “You see,” he said. “That’s why I always get a professional to handwrite important thank-you letters for me. In my hand, a brush is something to paint with.”

Master Taneya laughed. “Come to school,” he said. “We can train your hand, and maybe your mind.”

In Japan, calligraphy is most often associated with art. I remember well a large sheet of washi paper tacked to an easel, and when I say large, I mean at least four feet wide and eight feet high (I’ll let you translate that into metric measure). The calligrapher was armed with a very large brush, but one that was still maneuverable with one hand. At his side, sitting on the sand of the beach where the easel was set up, was a bucket of ink. My friend Shonosuke, 16th generation Noh drummer, started a solo performance, and as he caressed his drum and filled the night with his kakigoe shouts, the calligrapher wrote characters that Sonosuke’s performance pulled into his mind. It was spellbinding, and I wish I had a picture to show you.

I suppose that when the final line is drawn, each stroke of the brush transfers the emotion of the calligrapher onto the paper through the medium of carefully chosen brush and carefully prepared ink. It’s amazing.

Recent Posts

- Memorial Concerts “79 Roses” 05/12/2024

- Desire: The Carl Craig Story – Documentary, Music, Biography by Jean-Cosme Delaloye 29/04/2024

- Correspondent Jean-Cosme Delaloye also makes documentaries 14/02/2024

- American Express Previews: Gentlemen’s Sports 02/04/2019

- American Express Previews: Tennis & Golf 02/04/2019